I know very little about chess, and romance. Though I suppose maybe now more than I once did. Definitely more about chess. I’ve logged quite a bit of hours on Chess.com recently, and somehow I am still so, so bad. I know just enough to keep up for a bit but I can’t seem to close out a game. Makes me feel a bit stupid actually! No patience, no foresight. Such is my acquaintance with romance.

It’s been a bit of time since I last published something substantial on here. I’ve had bits and pieces of this essay stuck in my drafts (and in my head, and in my teeth) for months now. Everyone I know has heard about this mythical piece, attempting to speak of (maybe, vaguely) my love life. But every time I sit down to write it, it quickly devolves into something notably not about love and relationships—or, at least, not directly. I start writing about dating and suddenly I am writing about my friends, the internet, the President, my work, the downtown bus route, the laundry, Marxist theory, independent publishing houses, athleisure, Virginia Woolf, my parents, luxury smoothie brands, God, paying rent. I cannot seem to separate it out.

No better writer to turn to in these moments than Sally Rooney, who similarly cannot extract love and sex from the context it is borne from. Or born into. Or naturally, inextricably, a predestined part of. (See—complicated!) Her fourth novel, Intermezzo, manages to articulate a lot of this not-separateness I come across everyday, and the anxiety, the frustration, the beauty, the toil, the necessity of it all.

I preordered Intermezzo the second I could, read it the second I received it in the mail. It is her most mature, most grounded, most effecting, most about-chess yet. The story focuses primarily on the strained relationship between two brothers who recently lost their father to a long battle with cancer. Ten years apart, Peter and Ivan struggle seeing eye-to-eye, orbiting each other but never quite in harmony. Peter, the older, more well-adjusted, more successful brother, comes off arrogant and dismissive to Ivan, a lonely and struggling twenty-something (former) chess prodigy. Ivan resents his brother for not investing time into his relationships with himself and their late father. Peter carries the weight of responsibility with nowhere to rest. They argue. A lot. While their natural inclination is to deepen this divide, they are gently nudged back towards each other by the care and attention of their unlikely romantic partners. Ivan hesitantly enters a relationship with a recently separated woman fourteen years older than him. His brother uses his salary as a lawyer to support his much younger girlfriend, while still spending the occasional night at his ex-girlfriend’s house. That’s the plot at its simplest. The details, like any relationship, are more complicated.

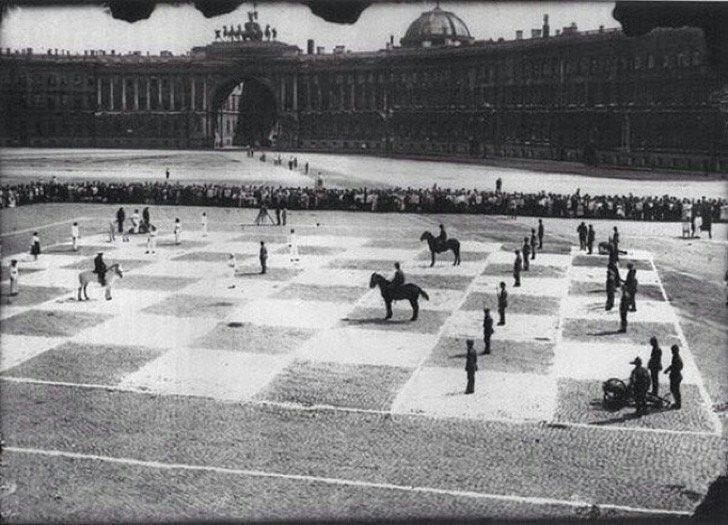

In chess, opening theory refers to the study of the beginning moves and strategy of a chess game. White has 20 options for opening moves. Black can respond with 20 in kind. There are over 9 million possible opening combinations after just three moves from either side. There are, theoretically, infinite games.

Something that keeps me returning to Rooney’s work is her ability to articulate universal experiences, and also, in the same breath, remind us that there is no one way to be. She illustrates unfamiliar dynamics and colors them with familiar sentiment. Peter’s younger girlfriend, Naomi, relies on him (and other men like him) for financial support. It’s a huge part of their relationship; Peter feels both guilty and comforted by her reliance on him, and struggles with how much he seems to need her in return. His ex-girlfriend, or rather, his first and probably true love, experienced a horrific accident when they were together, leaving her with chronic pain and an inability to commit to any physical relationship. The two women are vaguely aware of each other, empathetic towards the other because of their shared affection for Peter. Meanwhile, Ivan meets Margaret, a recently separated but notably still married thirty-six year old woman, and strikes up an unlikely romance that includes secret meetings and trips out of town to evade her alcoholic ex-husband and the whispers of the community. Nothing here is typical. Yet still, nothing here is particularly strange either. Often, in modern dating discourse, I see the immediate dismissal of any situation that doesn’t follow strict rules, deals directly with power, isn’t cleanly understood or explained. Maggie Nelson speaks about this in her book On Freedom:

“Even under the best of circumstances, sexual experience does not – indeed cannot – transfer in any simple fashion from one generation or one body to another. Each of us has our own particular body, mind, history, and soul to get to know, with all our particular kinks, confusions, traumas, aporias, legacies, orientations, sensitivities, abilities, and drives. We do not get to know these features in a single night, a year, or even a decade. Nor is whatever knowledge we gain likely to hold throughout the course of a life (or even a relationship, or a single encounter).”

Not to be dramatic or anything, but this seemingly simple observation single-handedly change so much of my perspective on dating and relationships. There is no one way to be.

And I’m not exactly on the cutting edge of journalism by saying we are situated right in the middle of a strange and unforgiving dating landscape. My friend and I show each other our Hinge profiles - they are such flattened versions of us they are barely anybody, just nobody’s that look a little bit like us. Still I pass through hundreds of profiles of other nobodys-resembling-somebody’s, hastily and with little grace. I laugh at what little they have to offer. But what could I possibly know? We are flattened to nearly nothing. We’ve already lost and we’ve barely started playing.

This abstraction of self makes it difficult to engage in any kind of meaningful reflection on what it is I desire or seek out of a relationship. Everything starts to feel a little too theoretical, not real enough. I get way too familiar with a man’s Instagram profile and suddenly I’ve mapped it all out. But, like Margaret says to Ivan: “Well, I think you’re comparing a scenario you made up in your head with a situation that has real people in it.” (182). Well okay then. Fair enough.

It is also ridiculously, horrifyingly, pathetically embarrassing. Don’t try to tell me it’s not if you’re not in it! I consider myself very secure and comfortable with myself, and still the consistent nagging of desire taps at me relentlessly, desperately.

“Pathetic, of course, but hadn’t he himself often felt pathetic, typing ‘hey, any plans tonight’ into an online messaging interface? Didn’t human sexuality at its base always involve a pathetic sort of throbbing insecurity, awful to contemplate?” (199).

Easier, then, to laugh at it all. As the resident single, 27-year-old in the friend group, I have become somewhat of a modern day court jester. Were I any bolder, I would go full Carrie Bradshaw and capitalize on the many absolutely hilarious stories I have from this past year alone, use them to become TikTok famous or something. In the meantime, I perform the same excruciatingly embarrassing stories to my friends over drinks as we laugh at all the absurdity of my relentless pursuit of love (and how one time I was ghosted by email. In the year 2024).

Rooney nails this absurdity, this pathetic-ness, this insecurity so well. She writes about love well because she writes about loneliness well, understands that loneliness is not just being alone, but also being in your house, at your job, on the sidewalk, in a restaurant, at the mall and alone. On the internet alone. About how the answer to not being alone is to not be alone. How that’s an annoying answer, and also the correct one. Okay, and there’s this issue of my body.

Of all of Sally Rooney’s merits, I do believe her understanding and use of the body is one of the strongest. She uses language to instigate a physical reaction, and it is immediate, violent. I feel the sorrow, feel the anxiety, feel the warmth, feel the comfort, all when they feel it, literally, physically, in my own body. Rooney makes reading feel like a full-contact sport. Ivan lashes out as his brother, he regrets the words as they are coming out of his mouth, and yet he cannot stop, cannot explain, cannot apologize. The moment roots itself in my gut—haven’t we all been there? The cadence of the descriptions of Peter’s daily life mimics quick and frantic breathing, and suddenly I am feeling similar anxiety and overwhelm. A new perspective on the material world—not only does it exist and build context around us, but our physical bodies require us to interact with it every day. And do I even point out the obvious? That the internet even further abstracts this concept of body? That I am so disconnected from the physical form I take that I am both unaware of its desires and also constantly bombarded with the relentlessly present general state of being? And also that body needs food, clothing, shelter.

This is the part where I share a secret. I want a boyfriend because I want to split rent. Of all the aching and longing for physical touch, emotional connection, quality time, cute pictures to post on Instagram, the thing that is legitimately tough to face is the deep envy that comes from watching my friends split the cost of their cute, downtown, nicely furnished one-bedroom apartment with their partner. I feel guilty for this feeling, to see what should be one of the most fulfilling relationships of my little life to be boiled down to something so mercenary, so transactional. But my cup is filled by my friends, my family, my career, my hobbies. These things are so lovely but I still have to pay all my bills. And it does affect the way I move through my life–how could it not? What is so wrong about wanting a sweet little spot with a person I love, easing some financial strain and allowing me relative comfort? I am so sorry to All Four Waves of Feminism, for reverting back to traditional necessities for marriage. It is not my fault. I am made to need this. Have you seen the price of a nice apartment these days?

Rooney is very clear in her politics. It is, in fact, what I respect most about her. Not only is she outspoken in interviews and essays, but she grounds her stories and characters in a modern political landscape that can be difficult to articulate and discuss. On rent:

“Of course, whether or not there is a beautiful woman in his life who enjoys being kissed by him, he still has to pay rent: he accepts this. Nonetheless, it is better to feel hopeful and optimistic about one’s life on earth while engaged in the never-ending struggle to pay rent, than to feel despondent and depressed while engaged in the same non-optional struggle anyway.” (150).

Non-optional struggle. Existing regardless. Might as well love somebody. But the pressure of external circumstances will always affect the way two people interact. All relationships are political. Separate that word from the colloquial use. Resort to Wikipedia: “the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals.” All relationships deal with power, collaboration, decisions, action again and again. I don’t say this to be discouraging. I say this to maybe inspire gentleness, humility.

Our five main characters all dance with each other. Think: a round of chess. Every movement pushing and pulling on each other. Within the context, playing the game. Still no one way to be. It is this gentleness, this humility, that ultimately leads Peter to one of Ivan’s chess tournaments. Being in space with one another. Every movement meaningful.

“Everything lethally intermixed, everything breaching its boundaries, nothing staying in its right place. She, the other, himself. Even Christine, Ivan, this married girlfriend of his. Their father: from beyond the grave. Conceptual collapse of one thing into another, all things into one. No. To answer first the simple question of where to sleep tonight.” (275)

Where to sleep tonight. Simple question.

This is not quite the essay on my love life I sought it out to be, but it’s a start, a kind of opening. Initially, I figured I could go my entire Substack career without ever touching the topic of dating and relationships, but it’s all intermixed. So we start here. There’s a line I think about often from Lydia Millet’s Dinosaurs: “That separateness was always the illusion.” That separateness was always the illusion! Frame it this way: infinite games. Reset the board. Open still, and then again. Go on in any case living.